xxx

Announcement

Collapse

No announcement yet.

Memoirs of a survivor

Collapse

This is a sticky topic.

X

X

-

Sweet Van: Genocide survivor has mother’s memories to sustain a long life

Sweet Van: Genocide survivor has mother’s memories to sustain a long life

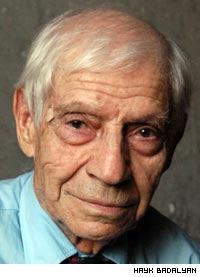

By Mariam Badalyan

ArmeniaNow reporter

Aharon Manukyan’s eyes widen when memories of his childhood take him back to his home in Van, then to an orphanage in Alexandrapol and the big, round chocolates of a Mr. Yaro, a patron of that orphanage.

Yerevantsi, but, always, Vanetsi

The orphanage became the boy’s home when he became exiled like so many thousands who were chased from their homes during the 1915 Genocide. Not so many survivors remain these 90 years later. Aharon was only 1 year old when his family was run out of their home. His account of deportation relies on stories told by his mother.

His 91 year old face shows all its age, when he retells his mother’s account . . .

The Vanetsis put up a fight against Turkish invaders, aided by Russian forces. But when the Russians pulled out, the 200,000-strong Armenian population left for Eastern Armenia. Aharon’s father died during the battle to save Van.

“My mother passed the deportation path with me on her arms and (brothers) Meliqset and Vahram pulling on her skirt,” Aharon says. “When we were crossing the river Euphrates it was very red, and the water carried corpses.”

Aharon’s mother, Mariam, hid their family valuables in her father’s grave in Van, then set out on foot with the three children for Echmiadsin (about ??? kilometers). There, she had to beg for food to keep the children alive. Soon, she took the children to the orphanage in Alexandrapol (now Gyumri), then returned to Echmiadzin to look for a job.

Aharon remembers the years spent in the orphanage.

“The orphanage belonged to an American couple. The husband’s name was Mr. Yaro and the wife’s name Miss Limin,” Aharon says, pronouncing names of orphanage trustees like a five-year old child, distorting the pronunciation. “They were very kind people. They lost their only child and devoted all their love to the orphanage children.”

He lists the orphanage food as if so many decades had not passed since he ate them: milk, soup, gata, halva, dried fruit. The orphanage seemed a paradise for a child who passed through starvation.

“It was only once that I did not go to school. I had a sore throat and I did not feel like going to school. There was an American whose name was Miche. When children did not want to go to school the mother-superior, Sandukht, the orphanage headmistress, called Miche. Miche came, took out my trousers and, thrashing, drove me barefooted through snow to the school entrance,” Aharon smiles. “This was the last time I was absent from school.”

The American couple adopted Aharon and his brothers and intended to take them to the United States. Aharon’s mother learned about it and rushed to the orphanage. She had found a job in Yerevan and could take the children with her.

“My mother was in charge of technical services at a laundry in Yerevan. In a short while, Mrs. Limin came. She offered 40 pieces of gold for my mother to let me go with her to America. She told my mother that I reminded her of her dead son. But my mother refused,” Aharon laughs naughtily. “I would be a wealthy man now. They say Mr. Yaro had 200 offices in America.”

Aharon has bright memories of his mother. During her whole life Mariam told endlessly about the town of Van – the Armenian districts of Aygestan and Qaghaqamech, churches, the town fortress, Armenian habits and culture.

“My mother told us,” Aharon remembers, “that during windy days water in the lake rose and fish, which were thrown ashore, moved to the town through rivulets. People caught them very easily. Tarekh (herring) was a very tasty fish. And in the nearby village of Artamet, a type of very sweet apple called bagyurmas, grew. One of such apples weighed more than a kilo.”

“My father never misses a chance to speak of Van,” says Aharon’s daughter Ruzan, 47. “For example whenever we eat fish he says: ‘you should have eaten tarekh (herring) from Lake Van’. We all know he also has never had it, but we understand that it is very important for him to speak of Van. It is kind of paying tribute to his homeland and to my grandmother.”

90 years after exile

Aharon looks at nowhere and smiles. He is not in the room, but moved to his past now and like a film come episodes from his life and his mother’s image . . .

“There was a hot spring coming from underneath St.Virgin Church,” Aharon repeats what his mother had told him. “Every kind of sick person came and took a bath in the water and was healed. People threw gold pieces into the water as a payment for their wonder healing.

“My mother, although uneducated, was a very kind and wise woman. All my life I have been reading and learning things, however the values I have had in my life come from my mother - good manners, honesty, kindness. These I passed to my four children.”

In 1945, inspired from his mother’s stories and the family’s fate, Aharon graduated from Yerevan State University in the faculty of history. And he never forgot that he is Vanetsi.

He says he is partly satisfied, knowing that this year some European states formally acknowledged as fact the Armenian Genocide. He dreams of seeing the day when Turkey will be called to account for those atrocities.

His glance is again far away in the past, and he sometimes smiles indulged in sweet memories. And sometimes frowns from a history that has given him the label of “survivor”."All truth passes through three stages:

First, it is ridiculed;

Second, it is violently opposed; and

Third, it is accepted as self-evident."

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860)

-

Bridges: A Survivor Remembers A Father's Good Work And A Turk's Kindness

By Marianna Grigoryan

ArmeniaNow reporter

Red and white grapes twist in the old man's hands, slipping into the bowl.

Andranik Tachikyan begins separating the sweet tasted bunches of grape - one

to eat, one to make wine.

He was a small child when he used to take bunches into his hands squeezing

them and having fun of it.

Andranik's family was well known in the Turkish city of Tripoli (now in

Lebanon).

His parents and ancestors, Andranik says, were wealthy famous people

possessing a big garden, a pharmacy, endless fields of wheat and tobacco and a

mansion that they lost in one day when the mass extermination of Armenians

began.

`My father was Dutch, his name was Pierre Van Moorsel. He was a famous man, a

doctor and engineer, who had built several bridges,' tells Andranik, taking

his father's visit card from a pile of papers. `My mother was Armenian, her

name - Arshaluys. She was a kind woman, who lost almost everything during the

genocide and stood against all the pain and trouble alone.'

`When the bridge was ready all our family used to sit under the brand new

bridge and loaded cars used to pass over it,' remembers Andranik, who is now

94. `That was the way and the bridge builder knew that building a bad bridge

will first of all threaten the life of his family. But everyone knew about the

strong bridges my father used to build. We were confident nothing will happen

to us, but neither his fame nor his descent saved him.'

Fixing his eyeglasses Grandpa Andranik brings the military green tie and

garment into order and begins bothering with his documents.

The old man who served in the Military Registration and Enlistment Office for

55 years tries to substantiate everything he says, bringing arguments showing

the shabby-yellow documents or photographs.

`This is the only picture of the massacre times,' he tells. `This is the only

thing that has remained from our wealth, years and life.'

Mother Arshaluys is in the middle, and Andranik and his sister Mariam are on

the sides.

The faded photographs are as old as the fading remembrance, the childhood

memories and difficulties of genocide times.

`I was small; there are some dates and names I can't remember, but there are

several things I remember very well,' tells Andranik. `The Turks on horses

with swords in their hands either killed people or threw them into the river.

The scene was horrifying. Although my father was a Dutch, they killed him and

my older brother as Armenians. We were shocked and horrified. We did not know

where to go and what to do without father. We left home, fame, wealth and took

the way of refuge - starving and barefooted.'

Andranik remembers their gardener, a Turk, reached them in a difficult moment

and `saved us away from the sword'.

`Our Turkish gardener was very loyal to my father and our family, because we

treated all of them very well. As soon as the massacres began, he saved us,

endangering his own life. He took my mother, my sister and me under a bridge

my father had built,' he says. `Everything went wrong, people could not save

their children from the Turks' swords; we would not survive if it were not for

the gardener.'

Andranik remembers the grass was high under the bridge and the gardener kept

them there.

`We stayed there for a while. Every day our gardener would secretly bring us

sunflower seeds, hazelnut oil cake and we ate it until the Americans entered

Tripoli,' he says. `Then the Americans found us and sent us to Greece by sea.'

Andranik says he remembers the orphans and the exhausted people gathered by

the ship.

`Everyone cried by the ship, for they couldn't believe they have been saved at

last. My mother would also cry, she would squeeze us to her breast and cry

loudly,' he remembers. `Then the ship took us to Greece. We move to Armenia

from Greece.'

Andranik says they saw many difficulties in Armenia at the beginning.

`We had a marvelous big house in Tripoli and lived in gorgeous conditions.

When we came to Armenia we were allotted an barn in one of the suburban

sovkhozes (state farms) of the city.'

And then he adds: `But we were happy we were alive.'

`Although my mother never forgot our house, my father and my brother, however,

after many years, life changed and we started everything over again. We worked

and had a home; we married and tried to live and to continue our life in the

Motherland.'"All truth passes through three stages:

First, it is ridiculed;

Second, it is violently opposed; and

Third, it is accepted as self-evident."

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860)

Comment

-

Peace is Only a Name: Aghavni recalls the far reaching effects of separation

By Ruzanna Tantushyan

ArmeniaNow reporter

Her name, Aghavni, means “Dove”.

It is a name meant, also, to symbolize the soul and peace.

“Dove”

In 1915, at the age of four, Aghavni the little dove found her place of peace in an orphanage in Lebanon. Like thousands, Aghavni Gevorgyan was separated from her family when invasions by Turks made orphans of Armenian children. “Little Dove” was sent to a home for children, founded by Americans and Danes.

She had been there eight years when word came that she had a brother, who was waiting for her outside the orphanage gates.

“What is a bother?” little bird asked. “Brother is a close relative,” explained her teacher.

Aghavni remembered that she had a brother. But the young man outside the orphanage was not someone she recognized. Aghavni resisted his hugs. After finding out the “brother” was not married, the headmaster did not allow him to take little Aghavni away although she had reached the age when the children usually were to leave the orphanage.

In fact, Aghavni had two brothers, both of whom she was separated. One, Hovhannes, settled in France, never to see his family again.

Aghavni’s cousin, Armenuhi, also was living in Lebanon. One day she recognized Aghavni among the orphans. And another new “nest” was found for Little Dove.

Sometime later – and 17 years since disappearing – a more familiar face returned to Aghavni’s life.

A photo with her mother reminds her about their reunion in 1932, and still brings tears of joy to Aghavni’s 96 year-old pale cheeks.

“My mother had a scar on her neck. I used to ask her what it was and how it had happened,” Aghavni recalls. “It was only when I had my second child that she told me the cruel story of it.”

She had a gold chain on her neck. During the resettlement, the Turks wanted to tear it off, but could not. It was an old peace of jewelry made by Armenian artisans and it did not come off easily. As a result of Armenian craftsmanship good job and the cruelty of Turkish regulars, her mother came to wear a scar instead of a gold chain.

In 1933, Aghavni married Gevorg in Aleppo. Gevorg was from Western Armenia and was rescued by a family of Turks who were sympathetic to the Armenians.

He learned about being an Armenian from a Turkish boy who named him “Gyavur”. The mistress of the house where he lived explained him that “Gyavur” meant Armenian.

“What is Armenian?”

“You are.”

“In that case where is my mother . . .”

This is how the boy of about 12 learned about his ethnicity and had so many questions, answers to which he thought he could find only in his village. The quest for the answers led him back to his village, his aunt’s house and his sister.

Aghavni interrupts her story here saying, “Old people talk much and the more they talk the more grief you learn.”

Aghavni and her husband moved to Armenia in 1946, bringing their 6 children with them. They had three more in the motherland. They rented an apartment in Arabkir district near a dry cleaners.

They had hardly moved in when a young woman came with a request to fix the key of a suitcase. They were lucky since Aghavni’s husband, Gevorg, was a craftsman and could repair nearly everything. But even luckier was Aghavni, as the woman was to travel to Western Armenia, and could bring some news from Aghavni’s brother whom she lost after 1915. And she did.

Aghunik (a term of endearment) also tells the story of her younger brother, Hakob, who was also saved after Turkish attacks. Saved, like Gevorg, by Turks. And remembered, like her mother, because of a scar.

The scar would mark his face when he together with his brother were helping their father to shoe the horse. Little Hakob was not strong and skilled enough to hold the horse’s leg and the horse kicked him.

Once again, a Turkish subject lent a helping hand to Aghavni’s family. One of the Turkish shopkeepers burned horse’s mane and put it on the child’s eye, saving it. After Turkish attacks started, the same man paid a Kurdish man several gold coins for him to take the boy across the Euphrates and threatened that he would find him and kill him in case he didn’t take the boy away. Hakob was saved.

He moved to Armavir, Krasnodar region in Russia and found a sellers’ job in an Armenian's shop and settled down. He married the shopkeeper's daughter. They had two children.

In 1937, there was an announcement according to which all those who wanted to leave the country were free to go in 24 hours. Hakob did not. He had a family and he was already settled down. Nevertheless, he managed to send a note that he made on a cigarette paper where he wrote, “The wound above my eye is cured”. The note reached Aghavni and she knew he was alive. However, they never met.

Aghavni had nine children. Five of them are now alive, but only three live in Armenia. She lost contact with her brother and nephews who are now in Russia and France. Those in France know little Armenian and cannot keep in touch.

The one named Little Dove has tried to bring her family together. It seems, though, that the events of 90 years ago are too far reaching, even after wounds have become scars ...Attached Files"All truth passes through three stages:

First, it is ridiculed;

Second, it is violently opposed; and

Third, it is accepted as self-evident."

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860)

Comment

-

Hayastan: “ . . . so much pain and sorrow . . .”

By Zhanna Alexanyan

ArmeniaNow reporter

“so much sorrow . . .”

Hayastan Basentsyan has twice taken the path of refuge.

Now; at age 95, she remembers the first . . .

“The refuge of 1914 is in my mind. We ran away because Turks were slaughtering us. We were hungry and thirsty… it is still before my eyes. It was (Armenian resistance leader) Serob Pasha who defended us,” remembers Hayastan – named for her country.

A smile lightens her face when she tells about Serob Pasha and General Andranik, heroes of the Armenian resistance. She saw them 91 years ago and has an image of them now from her road to refuge. She gets a proud stance and begins singing:

“A group of riders came down the mountains –among them Serob – the Armenian light,

A group of riders came down the mountains – among them Andranik – the Armenian king.”

“We spent 3 years at Ghaltakhchi when we came from Ergir (Armenians call the lost historical area of inhabitance in Western Armenia Ergir or Yerkir – which literally means “The Country” in Armenian.) Again we were told to return – and we went back. Those who were clever enough did not return. My father was in good relations then with the Turkish pasha; he used to come and go,” this is how Hayastan explains their return to Ergir.

The Basentsyans took the path of refuge for the second time in 1918. They were of Mush descent. Hayastan, 8, was the only child of her parents, and they lived in one house with uncles and their families. Few of them survived on the road. A child or two survived from the large family of Hayastan’s uncle.

“When we took the way of refuge my father said leave everything and run. My uncle wouldn’t come, saying he would not leave his father’s home and go. A Turk killed him, plunged his hand into his hair, twisted, and pulled the skin.

Shadows of the past are never far behind

“We left home and means and ran away barefooted. My father said take only bread with you. We went through at daytime passing the river on the boat in the night. Turks had burnt the bridge. Pair of families died that way, the others were killed, slaughtered, burnt. Turks would bind people with chain, pour oil on them and set the fire. Turks dressed Armenians in black…”

Hayastan says she hasn’t had an opportunity to talk about the massacres of those years for a long time and now telling, she feels it all again; events and pictures come before her eyes. The old woman weeps.

“Things Turks did to Armenians…killed infants and hoisted on bayonets, forcefully took away beautiful girls and women from their houses. There were no ways out; there were no means for escape for Armenians. Ahead was the river, behind were the Turks. Armenians threw themselves into the river and died. What can you do?” tells Hayastan and says it is in fact impossible to describe the horrifying scenes.

“No matter how you ask me, how you write, you cannot imagine in full for you have not seen. Those who have seen are not alive. How you can draw attention to what happened, there are no witnesses.”

She vividly remembers her grandfather, his home always open to the guests including Turks. She gets excited.

“I would die for the soil and water of Ergir. There was not a single day some ten Turks wouldn’t visit my grandfather’s place. He died on the way. They dug the snow and buried him in it. My grandfather would say: ‘Let my family run away and die in some other place, but let it escape the Turks]. My grandfather was a man of honor.”

Survivors are a diminishing link to a generation that needs remembering

Hayastan recalls their settlement – Buranugh Gharalyghi in Mush, their big house and the garden. She was born and baptized in that house.

“My daughter wanted us to go and see our land and water. What will I see if I go? Shall I see the mill standing, shall I see the shop standing, shall I see the house standing, what shall I see, tell me?” she asks.

Hayastan Basentsyan does not want to go and see an Ergir that is not hers and is ruined now. She loves her memories and does not want to depart from them.

“Many things were left to Turks. Our soil and water… Do you know what lands have the Turks got? It was such a good soil; manna would come down from the sky. Everything is now in the Turks’ hands.”

After getting married Hayastan Basentsyan moved to the village of Mrgastan, near Echmiadsin with her husband, Ruben. In 1941 her husband went to fight World War II and did not return. She raised three children alone. During the last years she lost her two sons and her daughter one after the other.

“People say some one dies of sorrow. Why then does God not take my soul – I have so much pain and sorrow?”Attached Files"All truth passes through three stages:

First, it is ridiculed;

Second, it is violently opposed; and

Third, it is accepted as self-evident."

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860)

Comment

-

Marie J. Simonian;Nurse, Armenian Genocide Survivor

The Washington Post

October 29, 2005 Saturday

Final Edition

Marie J. Simonian, 96, an orphaned survivor of the 1915 Armenian

genocide who became a nurse and physiotherapist, died of a stroke

Oct. 23 at Montgomery Hospice Casey House. She was a Rockville

resident.

Mrs. Simonian was born in Deort Yol, Cilicia, in western Armenia in

1909 and was orphaned six years later, during the period when as many

as 1.5 million Armenians died at the hands of Ottoman Turks. She grew

up in a British Quaker missionary orphanage in Beirut and was one of

the first Armenian women to graduate from the American University of

Beirut's nursing school.

Mrs. Simonian married and studied in London, where she received a

diploma in physiotherapy and worked in the field. She and her husband

immigrated in 1975 to the United States, where their children were

living, and settled in Prince George's County and later Rockville.

She plunged into work for her church, St. Mary's Armenian Apostolic

Church in Washington, and the Diocese of the Armenian Apostolic

Church of America. She also was a member of the Armenian General

Benevolent Union, the Armenian Assembly of America and the Armenian

American Wellness Center in Yerevan.

She urged her family to build character through moral courage, hard

work and love. She was proud of her family's academic

accomplishments, which include nine doctorates, seven master's

degrees and 24 bachelor's degrees. Fifteen family members became

presidents of their own companies or nonprofit organizations, and

eight are published authors.

Her husband of 67 years, John Simonian, died in 1998.

Survivors include four children, Dr. Simon Simonian of Potomac,

Cecile Keshishian of Los Angeles, Rita Balian of Arlington and Annie

Totah of Potomac; 11 grandchildren; and 12 great-grandchildren."All truth passes through three stages:

First, it is ridiculed;

Second, it is violently opposed; and

Third, it is accepted as self-evident."

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860)

Comment

Comment