Re: Is Russia a Banana Republic?

Russians Who Invested in 'People's IPOs' See Their Savings Vanish

By Philip P. Pan

Washington Post Foreign Service

Friday, December 12, 2008; A01

MOSCOW -- Anatoly Sisoyev always considered himself a patriot. As a child, he lost his father to an accident in the Soviet space program. As an adult, he served 30 years in the military, retiring at the rank of major. His son followed him into the army and was killed in Chechnya at the age of 18.

Through it all, he said, his faith in the Russian government never waned.

So when he heard radio ads two years ago encouraging citizens to invest in the initial public offerings of state-owned companies, Sisoyev lined up to buy shares, first in the oil-and-gas giant Rosneft and a year later in the nation's second-largest bank, VTB.

Sisoyev had suffered in Russia's rocky transition to capitalism, but the "people's IPOs," as they were billed by the Kremlin, seemed different. Then-President Vladimir Putin endorsed the stock offerings, presenting them as a chance for ordinary Russians -- and not just the wealthy -- to own a piece of the booming economy.

Now, as Russia confronts its worst economic crisis in a decade, the value of Sisoyev's shares has plummeted, wiping out most of his life savings. At 65, he is working as a part-time security guard because food prices are climbing faster than his meager pension. In a recent interview, he buried his face in his hands and fought back tears as he explained how he is trying to treat his sick wife by reading old medical textbooks because he can't afford a good doctor.

"I believed in the state, especially under Putin, so I bought shares," said Sisoyev, a soft-spoken man with white hair and a soldier's posture. "Now I don't believe in anything."

Swayed by years of steady growth -- and by an aggressive, state-funded marketing campaign -- hundreds of thousands of Russians ventured into the country's young stock markets to buy shares in the "people's IPOs." Now these first-time investors, many of them elderly pensioners like Sisoyev, are among those suffering the most as Russia's economic problems enter into a more painful phase.

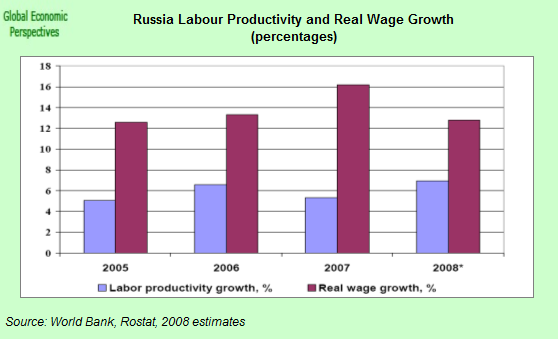

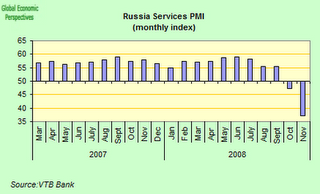

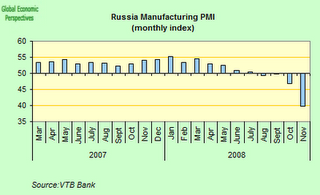

Limited largely to the financial sector and the wealthy elite at first, the crisis is beginning to be felt by the broader population. Inflation, wage arrears and unemployment are on the rise, and in a recent survey, one-fifth of Russians said they or a family member worked for a company that had announced layoffs.

Putin, now prime minister, has responded largely by channeling funds into the banking system and providing emergency loans to the billionaires, known as the oligarchs, many of whom are struggling to pay debts to foreign creditors. The bailout has allowed the Kremlin to take greater control of industries that Putin has long argued never should have been privatized after the fall of the Soviet Union.

But as the state spends tens of billions of dollars aiding and gaining leverage over these tycoons, it has all but ignored the ordinary Russians who invested in the "people's IPOs." They present a political risk for Putin because their situation undermines the narrative he has used to win support and consolidate power -- that of the strong leader who delivered broad-based prosperity to Russia after years of turmoil during which oligarchs plundered the state.

The "people's IPOs" were designed in part to reinforce Putin's populist image. The three state firms involved -- Rosneft, VTB and the nation's largest bank, Sberbank -- could have done what companies going public usually do and focused on the institutional investors and wealthy individuals who own the vast majority of trading shares in Russia. Instead, Putin publicly instructed the firms to make sure the masses could buy stock, too.

The economic goal was to expand the country's tiny base of retail investors and develop its fledgling stock markets. But the approach also allowed Putin to draw a contrast with the chaotic privatization efforts of the 1990s, during which a small number of entrepreneurs took control of assets worth hundreds of billions of dollars.

In Rosneft's case, the IPO was also seen as part of a strategy to legitimize the company's controversial acquisition of the assets of the Yukos oil empire after the Kremlin jailed its chief, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, then Russia's wealthiest man and a prominent Putin critic.

Some foreign investment funds declined to put money into Rosneft because of legal and moral concerns -- critics compared the IPO to buying stolen goods -- but many Russians like Sisoyev saw its control of the Yukos oil fields as a selling point.

"I was hoping for justice," Sisoyev recalled. "With all the natural resources in the country, our lives should be much better. Instead, only a few people had benefited. I hoped the IPO meant a more fair distribution of profit."

Rosneft sold 15 percent of its shares in London and Moscow in July 2006, raising more than $10 billion. The "people's IPO" represented only a fraction of the total but exceeded expectations, with 115,000 people investing $790 million. Lines were so long the company said it could have raised three times as much if it had extended the deadline for purchases.

Nine months later, about 46,000 people purchased $800 million in shares in the IPO of Sberbank. Then, in May 2007, VTB staged the largest "people's IPO," raising $1.5 billion from 131,000 investors. Bank branches in more than 100 cities stayed open late and on weekends to meet the demand.

Sisoyev invested about $8,400 in Rosneft and VTB, almost all he had managed to set aside after the 1998 financial crisis wiped him out. The amount equaled 2 1/2 years of payments from his military pension.

"I was desperate to save money," he said, adding that he was wary of putting his nest egg in a bank and that inflation was destroying its value. "I needed to secure it, especially for retirement, because I knew my ability to earn money would decline." At the same time, his family's medical expenses were rising. His wife had suffered two heart attacks, and doctors told him he needed a spine operation.

The "people's IPOs" seemed like a safe investment, Sisoyev said, because the government was the majority shareholder and he believed it would never let the stock price fall too far. An upbeat ad campaign that appealed to patriotism and highlighted the companies' potential for growth reinforced that impression.

According to Russian media reports, the state spent millions marketing the IPOs. In one ad, a farmer building a new house explains his success to a neighbor digging up potatoes. "An IPO is when entirely new shares are sold in the market at a fixed price," he says. "In a few years, the business climbs and the shares go up. It is very profitable."

"What a life," the neighbor responds. "Some get everything, others nothing!"

Though the vast majority of Russians decided against investing, those who had heard more about the IPOs were much more likely to buy shares, according to a survey by the National Agency for Financial Research examining the impact of the campaign. "State support" for the bank was among the top reasons cited.

"I was hooked by the advertising," said Elvira Kudryashova, 66, a pensioner in Volgograd who invested her life savings in VTB and now struggles to make ends meet as a part-time teacher. "I didn't understand anything about the process. . . . To me, it was a safe investment because it was backed by the state."

Putin has been closely associated with the IPOs. In December 2006, he was shown on television telling finance officials to do everything possible "to give people the chance to buy these shares." At a news conference two months later, he cautioned that "investing in securities is always risky" but added: "The economic foundations of our national companies are very sound, and all those who have made an initial stock offering are stable economic actors. . . . I have no doubts that these are good investments."

In April 2007, VTB announced its IPO at the presidential residence. "Tens of thousands of citizens will be able to become shareholders," the bank's chief, Alexei Kostin, told Putin. "This is the goal you have set, and I hope we will reach it."

When VTB shares began slipping weeks later, Kostin urged patience and told investors the government would "step in to prop them up." But as the global financial crisis has hit, Russia's stock markets have fallen harder than most, and VTB is now down almost 80 percent from its IPO price. Sberbank has fallen nearly as much, and the value of Rosneft shares has declined more than 50 percent.

Public anger has been evident at shareholder meetings, with crowds filling conference rooms to berate company executives, including Deputy Prime Minister Igor Sechin, the Rosneft board chairman and one of the Kremlin's most powerful figures. Shareholders have accused the firms of corruption and waste, questioned the salaries of executives, and demanded higher dividends and a buyback of their shares at the original price.

"These IPOs made sense in theory, but they wanted the money without the responsibility, without recognizing the rights of shareholders," said Alexei Navalny, a lawyer and political activist who has been organizing minority shareholders. "Naturally, an investment is a risk, but the state is the main shareholder of these firms and is responsible for their performance. So the state should at least begin discussing buying back shares."

Sberbank and VTB did not respond to written questions. Nikolai Manvelov, a spokesman for Rosneft, defended the "people's IPO" as "the first example of a completely fair and transparent privatization process in modern Russian history."

"The fact that the Rosneft share price is currently significantly below the IPO level is due to the global financial crisis and has nothing to do with the fundamentals of the company," he said, noting that the stock was outperforming its main Russian rivals.

Sisoyev, whose shares are down 60 percent, said he has tried to contact Putin several times to plead for help, without success. "There was so much anger that now I'm sort of numb and fed up. I don't know what I'll do," he said. "If I had the money, I'd move to another country, maybe Germany. I have friends there, and they say those we defeated in the war now get pensions 60 times those of the victors."

Researcher Anna Masterova contributed to this report.

Russians Who Invested in 'People's IPOs' See Their Savings Vanish

By Philip P. Pan

Washington Post Foreign Service

Friday, December 12, 2008; A01

MOSCOW -- Anatoly Sisoyev always considered himself a patriot. As a child, he lost his father to an accident in the Soviet space program. As an adult, he served 30 years in the military, retiring at the rank of major. His son followed him into the army and was killed in Chechnya at the age of 18.

Through it all, he said, his faith in the Russian government never waned.

So when he heard radio ads two years ago encouraging citizens to invest in the initial public offerings of state-owned companies, Sisoyev lined up to buy shares, first in the oil-and-gas giant Rosneft and a year later in the nation's second-largest bank, VTB.

Sisoyev had suffered in Russia's rocky transition to capitalism, but the "people's IPOs," as they were billed by the Kremlin, seemed different. Then-President Vladimir Putin endorsed the stock offerings, presenting them as a chance for ordinary Russians -- and not just the wealthy -- to own a piece of the booming economy.

Now, as Russia confronts its worst economic crisis in a decade, the value of Sisoyev's shares has plummeted, wiping out most of his life savings. At 65, he is working as a part-time security guard because food prices are climbing faster than his meager pension. In a recent interview, he buried his face in his hands and fought back tears as he explained how he is trying to treat his sick wife by reading old medical textbooks because he can't afford a good doctor.

"I believed in the state, especially under Putin, so I bought shares," said Sisoyev, a soft-spoken man with white hair and a soldier's posture. "Now I don't believe in anything."

Swayed by years of steady growth -- and by an aggressive, state-funded marketing campaign -- hundreds of thousands of Russians ventured into the country's young stock markets to buy shares in the "people's IPOs." Now these first-time investors, many of them elderly pensioners like Sisoyev, are among those suffering the most as Russia's economic problems enter into a more painful phase.

Limited largely to the financial sector and the wealthy elite at first, the crisis is beginning to be felt by the broader population. Inflation, wage arrears and unemployment are on the rise, and in a recent survey, one-fifth of Russians said they or a family member worked for a company that had announced layoffs.

Putin, now prime minister, has responded largely by channeling funds into the banking system and providing emergency loans to the billionaires, known as the oligarchs, many of whom are struggling to pay debts to foreign creditors. The bailout has allowed the Kremlin to take greater control of industries that Putin has long argued never should have been privatized after the fall of the Soviet Union.

But as the state spends tens of billions of dollars aiding and gaining leverage over these tycoons, it has all but ignored the ordinary Russians who invested in the "people's IPOs." They present a political risk for Putin because their situation undermines the narrative he has used to win support and consolidate power -- that of the strong leader who delivered broad-based prosperity to Russia after years of turmoil during which oligarchs plundered the state.

The "people's IPOs" were designed in part to reinforce Putin's populist image. The three state firms involved -- Rosneft, VTB and the nation's largest bank, Sberbank -- could have done what companies going public usually do and focused on the institutional investors and wealthy individuals who own the vast majority of trading shares in Russia. Instead, Putin publicly instructed the firms to make sure the masses could buy stock, too.

The economic goal was to expand the country's tiny base of retail investors and develop its fledgling stock markets. But the approach also allowed Putin to draw a contrast with the chaotic privatization efforts of the 1990s, during which a small number of entrepreneurs took control of assets worth hundreds of billions of dollars.

In Rosneft's case, the IPO was also seen as part of a strategy to legitimize the company's controversial acquisition of the assets of the Yukos oil empire after the Kremlin jailed its chief, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, then Russia's wealthiest man and a prominent Putin critic.

Some foreign investment funds declined to put money into Rosneft because of legal and moral concerns -- critics compared the IPO to buying stolen goods -- but many Russians like Sisoyev saw its control of the Yukos oil fields as a selling point.

"I was hoping for justice," Sisoyev recalled. "With all the natural resources in the country, our lives should be much better. Instead, only a few people had benefited. I hoped the IPO meant a more fair distribution of profit."

Rosneft sold 15 percent of its shares in London and Moscow in July 2006, raising more than $10 billion. The "people's IPO" represented only a fraction of the total but exceeded expectations, with 115,000 people investing $790 million. Lines were so long the company said it could have raised three times as much if it had extended the deadline for purchases.

Nine months later, about 46,000 people purchased $800 million in shares in the IPO of Sberbank. Then, in May 2007, VTB staged the largest "people's IPO," raising $1.5 billion from 131,000 investors. Bank branches in more than 100 cities stayed open late and on weekends to meet the demand.

Sisoyev invested about $8,400 in Rosneft and VTB, almost all he had managed to set aside after the 1998 financial crisis wiped him out. The amount equaled 2 1/2 years of payments from his military pension.

"I was desperate to save money," he said, adding that he was wary of putting his nest egg in a bank and that inflation was destroying its value. "I needed to secure it, especially for retirement, because I knew my ability to earn money would decline." At the same time, his family's medical expenses were rising. His wife had suffered two heart attacks, and doctors told him he needed a spine operation.

The "people's IPOs" seemed like a safe investment, Sisoyev said, because the government was the majority shareholder and he believed it would never let the stock price fall too far. An upbeat ad campaign that appealed to patriotism and highlighted the companies' potential for growth reinforced that impression.

According to Russian media reports, the state spent millions marketing the IPOs. In one ad, a farmer building a new house explains his success to a neighbor digging up potatoes. "An IPO is when entirely new shares are sold in the market at a fixed price," he says. "In a few years, the business climbs and the shares go up. It is very profitable."

"What a life," the neighbor responds. "Some get everything, others nothing!"

Though the vast majority of Russians decided against investing, those who had heard more about the IPOs were much more likely to buy shares, according to a survey by the National Agency for Financial Research examining the impact of the campaign. "State support" for the bank was among the top reasons cited.

"I was hooked by the advertising," said Elvira Kudryashova, 66, a pensioner in Volgograd who invested her life savings in VTB and now struggles to make ends meet as a part-time teacher. "I didn't understand anything about the process. . . . To me, it was a safe investment because it was backed by the state."

Putin has been closely associated with the IPOs. In December 2006, he was shown on television telling finance officials to do everything possible "to give people the chance to buy these shares." At a news conference two months later, he cautioned that "investing in securities is always risky" but added: "The economic foundations of our national companies are very sound, and all those who have made an initial stock offering are stable economic actors. . . . I have no doubts that these are good investments."

In April 2007, VTB announced its IPO at the presidential residence. "Tens of thousands of citizens will be able to become shareholders," the bank's chief, Alexei Kostin, told Putin. "This is the goal you have set, and I hope we will reach it."

When VTB shares began slipping weeks later, Kostin urged patience and told investors the government would "step in to prop them up." But as the global financial crisis has hit, Russia's stock markets have fallen harder than most, and VTB is now down almost 80 percent from its IPO price. Sberbank has fallen nearly as much, and the value of Rosneft shares has declined more than 50 percent.

Public anger has been evident at shareholder meetings, with crowds filling conference rooms to berate company executives, including Deputy Prime Minister Igor Sechin, the Rosneft board chairman and one of the Kremlin's most powerful figures. Shareholders have accused the firms of corruption and waste, questioned the salaries of executives, and demanded higher dividends and a buyback of their shares at the original price.

"These IPOs made sense in theory, but they wanted the money without the responsibility, without recognizing the rights of shareholders," said Alexei Navalny, a lawyer and political activist who has been organizing minority shareholders. "Naturally, an investment is a risk, but the state is the main shareholder of these firms and is responsible for their performance. So the state should at least begin discussing buying back shares."

Sberbank and VTB did not respond to written questions. Nikolai Manvelov, a spokesman for Rosneft, defended the "people's IPO" as "the first example of a completely fair and transparent privatization process in modern Russian history."

"The fact that the Rosneft share price is currently significantly below the IPO level is due to the global financial crisis and has nothing to do with the fundamentals of the company," he said, noting that the stock was outperforming its main Russian rivals.

Sisoyev, whose shares are down 60 percent, said he has tried to contact Putin several times to plead for help, without success. "There was so much anger that now I'm sort of numb and fed up. I don't know what I'll do," he said. "If I had the money, I'd move to another country, maybe Germany. I have friends there, and they say those we defeated in the war now get pensions 60 times those of the victors."

Researcher Anna Masterova contributed to this report.

Comment