October 20, 2011, 6:30 pmNo Cellphone-Cancer Link in Large Study

By TARA PARKER-POPE Mary F. Calvert for The New York Times

Mary F. Calvert for The New York Times

What is the link between cellphones and cancer?

A major study of nearly 360,000 cellphone users in Denmark found no increased risk of brain tumors with long-term use.

Although the data, collected from one of the largest-ever studies of cellphone use, are reassuring, the investigators noted that the design of the study focused on cellphone subscriptions rather than actual use, so it is unlikely to settle the debate about cellphone safety. A small to moderate increase in risk of cancer among heavy users of cellphones for 10 to 15 years or longer still “cannot be ruled out,” the investigators wrote.

The findings, published in the British medical journal BMJ as an update of a 2007 report, come nearly five months after a World Health Organization panel concluded that cellphones are “possibly carcinogenic.” Last year, a 13-country study called Interphone also found no overall increased risk but reported that participants with the highest level of cellphone use had a 40 percent higher risk of glioma, an aggressive type of brain tumor. (Even if the elevated risk of glioma is confirmed, the tumors are relatively rare, and thus individual risk remains minimal.)

The Danish study is important because it matches data from a national cancer registry with mobile phone contracts beginning in 1982, the year the phones were introduced in Denmark, until 1995. Because it used a computerized cohort that was tracked through registries and digitized subscriber data, it avoided the need to contact individuals and thus eliminated problems related to selection and recall bias common in other studies.

However, the major weakness of the study is that it counted cellphone subscriptions rather than actual use by individuals, and failed to count people who had corporate subscriptions or who used cellphones without a long-term contract. Those small details could have diluted any association between cellphone use and cancer risk, the investigators conceded.

An accompanying editorial noted that although the results are reassuring, they must be viewed in the context of about 15 previous studies on cellphones and cancer risk, including those that did detect an association between heavy cellphone use and certain brain tumors.

Anders Ahlbom, a professor of epidemiology at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden and an author of the editorial, said in an e-mail that research on the subject should continue.

“Many stones have been lifted, but little has been found,” he wrote. “While there is little reason to expect anything to be found beneath the next stone, some uncertainty remains. We have learned that studies based on historical accounts of cellphone use are prone to bias. So a reasonable way forward seems to be to follow national statistics and prospective cohorts.”

By TARA PARKER-POPE

Mary F. Calvert for The New York Times

Mary F. Calvert for The New York TimesWhat is the link between cellphones and cancer?

A major study of nearly 360,000 cellphone users in Denmark found no increased risk of brain tumors with long-term use.

Although the data, collected from one of the largest-ever studies of cellphone use, are reassuring, the investigators noted that the design of the study focused on cellphone subscriptions rather than actual use, so it is unlikely to settle the debate about cellphone safety. A small to moderate increase in risk of cancer among heavy users of cellphones for 10 to 15 years or longer still “cannot be ruled out,” the investigators wrote.

The findings, published in the British medical journal BMJ as an update of a 2007 report, come nearly five months after a World Health Organization panel concluded that cellphones are “possibly carcinogenic.” Last year, a 13-country study called Interphone also found no overall increased risk but reported that participants with the highest level of cellphone use had a 40 percent higher risk of glioma, an aggressive type of brain tumor. (Even if the elevated risk of glioma is confirmed, the tumors are relatively rare, and thus individual risk remains minimal.)

The Danish study is important because it matches data from a national cancer registry with mobile phone contracts beginning in 1982, the year the phones were introduced in Denmark, until 1995. Because it used a computerized cohort that was tracked through registries and digitized subscriber data, it avoided the need to contact individuals and thus eliminated problems related to selection and recall bias common in other studies.

However, the major weakness of the study is that it counted cellphone subscriptions rather than actual use by individuals, and failed to count people who had corporate subscriptions or who used cellphones without a long-term contract. Those small details could have diluted any association between cellphone use and cancer risk, the investigators conceded.

An accompanying editorial noted that although the results are reassuring, they must be viewed in the context of about 15 previous studies on cellphones and cancer risk, including those that did detect an association between heavy cellphone use and certain brain tumors.

Anders Ahlbom, a professor of epidemiology at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden and an author of the editorial, said in an e-mail that research on the subject should continue.

“Many stones have been lifted, but little has been found,” he wrote. “While there is little reason to expect anything to be found beneath the next stone, some uncertainty remains. We have learned that studies based on historical accounts of cellphone use are prone to bias. So a reasonable way forward seems to be to follow national statistics and prospective cohorts.”

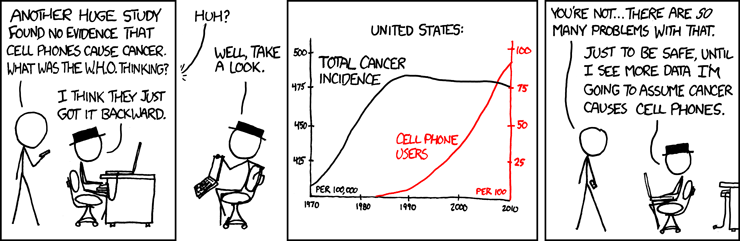

Love xkcd.

Love xkcd.

Comment